Key resellers have a reputation for being sketchy and potentially harmful to the game industry. Recently, the magnitude of their negative impact was shown.

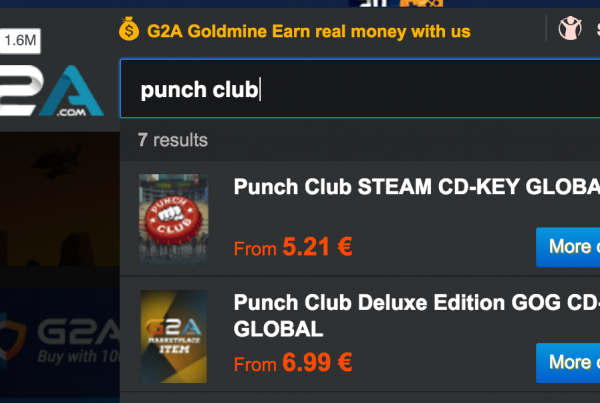

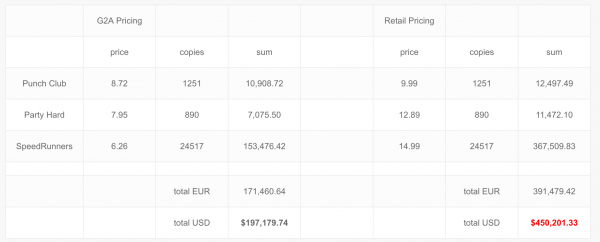

Earlier this week, tinyBuild, an indie game development studio and publisher, revealed that the key reselling site, G2A.COM, sold thousands of keys of their games without tinyBuild ever seeing a dime. Almost $200k was pulled in by G2A, though tinyBuild has noted that the keys sold at retail value would have been worth $450k.

tinyBuild’s calculations of sales and lost sales based on sales information from G2A.

G2A’s response to this reveal was not an apology, but demands that tinyBuild produce a list of the keys that are fraudulent (a rather difficult and absurd request), and a criticism of tinyBuild’s loss estimate, clearly not understanding what “retail value” means.

G2A.COM calls for tinyBuild to provide their list of suspicious keys within three days from the date of this transmission.

The CEO of tinyBuild, Alex Nichiporchik responded that:

The way our business works is we work with a ton of partners, and tracking down individual key batches is an insane amount of work. Even if we did that and deactivated certain batches, each one of them will have a bunch of ‘legitimate’ redemptions… I [also] believe [G2A would] just resell those keys and make more money off of it.

Alex’s distrust of key resellers is understandable, especially considering the response from G2A. Instead of taking down tinyBuild keys or providing compensation of the sales to the studio, G2A is still happily making money off of assisting scammers.

One of tinyBuild’s games, Punch Club.

Key resellers seem to have a pretty reasonable business model at first glance: a person gets a key for a game they don’t want or already have, and sells it on a key reselling website to make a few bucks and put the key in the pocket of someone who will use it.

The internet is not a kind place, though, and key resellers provide an opportunity for fraudsters to easily cash out. They use stolen credit cards to purchase keys, like from Humble Bundle and even key resellers, then turn around and resell them on the key reselling sites that are more lenient in their security. The key is resold and gone on to more legitimate hands long before the first seller is hit with the charge-back from the stolen card. Publishers and developers lose, while scammers and sketchy key resellers win.

“They’re basically helping people launder money” noted Mike Gnade, from IndieGameStand. “This scam really pisses me off – mainly because these people aren’t stealing from large rich corporations but taking advantage of smaller companies and indie developers.”

While stolen credit cards are a large part of the problem, there are other places that these key reselling merchants are finding keys: bots and scammers.

Bots happily search streams, Facebook and other channels for posted codes to snatch up and resell, and the losing side is always the developers. Not even the smallest game studios are free from these risks.

My inbox often gets emails like the following:

Hello!

My name is Anas, nice to meet you.I found in the Steam list your game Potions: A Curious Tale and would like to submit it on my channel.I plan to try your game on one of the my closest twitch-streams, and if I liked it – make a full review on YouTube channel.I will be very grateful, if you send me few extra keys as a small thanks for advertising (I want give them to my friends, who are just beginning to engage a streaming).Thank you for your time. I hope to hear your answer, even if it is negative.Twitch: http://www.twitch.tv/lebledart

With an unreleased game, I am particularly sensitive to requests like this, because the game is not intended to be released to the general public yet. Reselling of my keys would be extremely harmful to Potions: A Curious Tale, not just due to lost revenue, but because the game is unfinished and may be received poorly.